Chinese technology companies are now world leaders in areas such as artificial intelligence, e-commerce and fintech. After investing heavily in South East Asia, they are rapidly establishing themselves in India, with venture capital firms following suit.

This can have a transformative effect on the Indian technology scenario over time and catalyse an Operating System (OS) upgrade for the India-China relationship. The Indian government should encourage these developments, but also must move swiftly to enforce regulation that improves user data privacy and demand data localisation with guidelines on cross-border data transfer. This is critical if India is to realise the benefits of growth and innovation while also guarding against security risks.

Prime Minister Modi made his first visit to China in 2015 just as the Alibaba Group had made its maiden investment in Paytm and the potential for cross-border investments in this area was becoming apparent. The accompanying tables show that Alibaba has a consolidated lead. But it is now accompanied by the who’s who of China’s internet industry in fintech, e-commerce, ridesharing, content, and messaging, either through a stake in a local Indian company or directly through their own products.

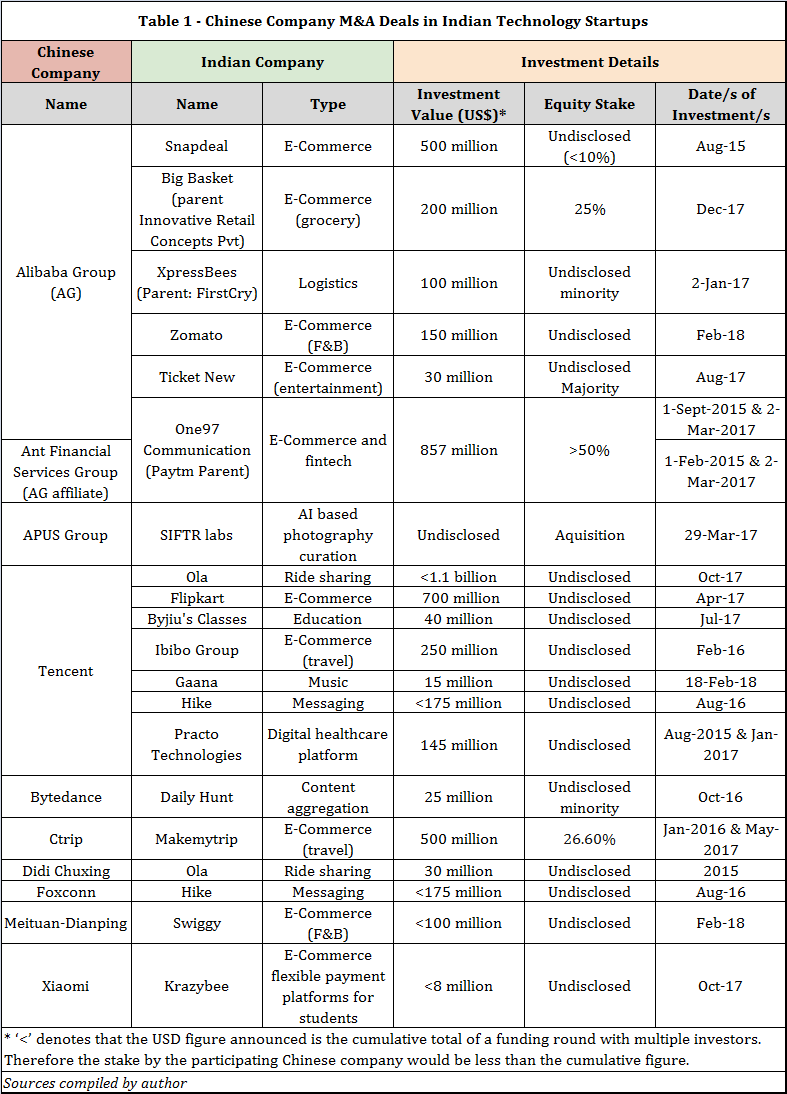

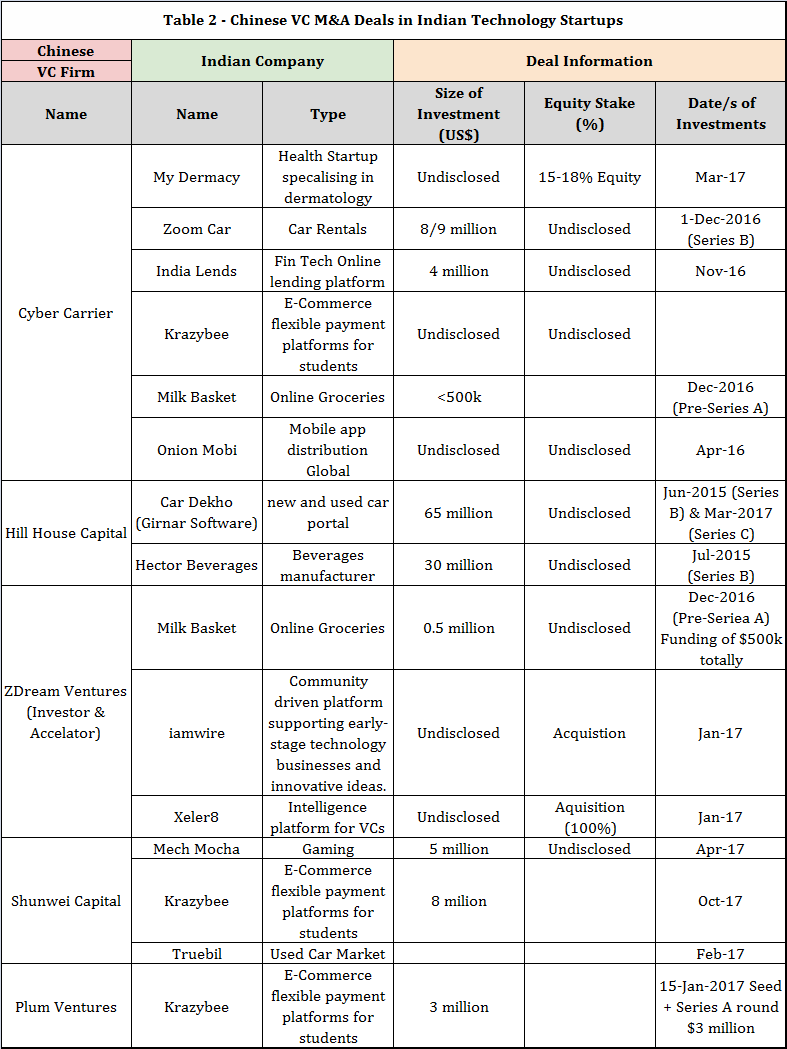

The cumulative Chinese investment in Indian startups is estimated to be between $4-5 billion, thus making it the largest source of Chinese investment in India in just two year, as Santosh Pai, a partner at Link Legal India Law Services and authority on Chinese investment in India, confirms. Their presence in the market can be divided into two categories: equity investments in Indian startups, or a more direct relationship, often through Indian subsidiaries. Table 1 & 2 captures investments in Indian startups with a company-by-company and deal breakdown.

Data available on an open-to-edit Chinese M&A activity in India tracker.

Giants and unicorns

The Alibaba Group (with affiliate Ant Financial), followed by Tencent, are the biggest, with investments in India’s most prominent unicorns, Flipkart, Hike, and Ola, bringing their rivalry to the Indian subcontinent. Alibaba’s investments dovetail neatly with its strategy to control what Jack Ma considers the ‘iron triangle of success’ – e-commerce, payments, and logistics – while Tencent’s investments in Hike, for instance, align with its super-app, Wechat. Likewise, three of China’s largest unicorns, Didi, Bytedance, and Meituan-Dianping, have each invested in their Indian counterparts.

On the VC front, upstart India-focussed funds, such as Cybercarrier, paved the way with a flurry of small investments, attempting to bring to Indian startups their capital and experience with scaling comparable business models in China. Now, more are following in their footsteps.

Yet others have taken a more direct route to Indian consumers, with Android apps, all popular in India, such as UC Browser (Alibaba-owned), Cheetah Mobile, and Cleanmaster, and content aggregators, such as Newsdog, among many others. The latest big ticket entrants are Ofo and Mobike: the big two dockless bike micro-rental companies in China are attempting to bring the bike-sharing phenomenon to Indian cities. Chinese Smartphone manufacturers, Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo, have been dominating the India market since 2016.

What does this investment mean for India?

The infusion of Chinese capital is an important new source of funding. It is also often accompanied by an access to technology and best practices in China that enables Indian entrepreneurs to compete with capital-rich Silicon Valley players. If implemented well, this can have positive effects all round.

First, Indian consumers benefit through products designed exclusively for their needs as opposed to U.S. imports. Second, India’s tech landscape can thrive, with local startups generating data that can help develop AI-based systems – from autonomous driving to AI assistants. This can solve problems in the Indian context and shore up value for the economy. New Delhi for its part, finds oversight easier for companies based within the reach of Indian law than those in the distant Bay area.

Chinese capital and technology are thus an opportunity for India to develop its own innovative tech giants – just as foreign investors did with China’s big three, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. The Indian government can leverage the strengths of Alibaba and Tencent to help its own entrepreneurs realise goals around digitisation, Smart Cities, and building AI infrastructure, just as it is doing with Google and Microsoft. Finally, professionals on both sides of the border can hereby collaborate, exchange ideas, and avail of a larger talent pool that is equipped with more knowledge and less prejudice. This kind of exchange was a key factor in the growth of China’s relations with Japan and the U.S. over the past few decades despite the existing geopolitical strain.

The involvement of foreign technology companies poses questions around data protection and management because access to data is central to the development of most AI-based technologies. Given the geopolitical tension between the two countries it is natural to expect an added layer of suspicion over access to Indian user data or the influence of the Chinese government. Reports of some Chinese apps leaking data to servers based in China is a concern, as is the record of lax security standards in apps, such as UC Browser, exposed by Citizen Lab researchers.

User data is the fuel that powers companies, driven by advertisement revenue and machine learning algorithms. It incentivises them to overlook security issues in the eagerness to acquire user data. The recent Cambridge Analytica-Facebook episode is a prime example. It is therefore critical for the Indian government to devise a coherent set of regulations around data protection, data localisation, and cross-border data transfer. Data generated in India, especially by Indian citizens, must be held in servers based in India, with strict stipulations on what can be allowed to be transferred out.

China’s own Cybersecurity Law, armed with a growing regime of standards and specifications, as well as the European Union’s, through its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (set to take effect in May 2018), are moves in this direction. In fact, due to the Cybersecurity Law, there are almost no restrictions keeping the government from accessing private data. It is naive to expect Chinese Internet companies to enter India and adhere to standards that don’t legally exist. There must be strict but clear safeguards that may borrow from these laws and regulations, designed keeping the Indian system in mind.

New engagement

India should view Chinese investment as a political opportunity and an asset. It offers scope for dialogue outside the rigidity of government channels. This calls to mind Jack Ma’s meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump just days after the election results, with Ma acting as both Chairman of the Alibaba Group and acolyte for President Xi Jinping. China is far from a monolithic entity and Xi is beholden to a number of interest groups.

The People’s Liberation Army is known to play a highly influential role in dealings and policy formulations pertaining to India. In the long run, having these influential technology companies – nearly all new members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference are from the technology industry – invested in a healthy relationship with India potentially offers a counter-balance. In the past few years there has been a sharp push by the Party towards greater fusion with the private sector, with companies setting up Party cells amidst suggestions for State investment as a form of mixed ownership. It is in the Indian government’s interest to actively leverage these developments

The bilateral relationship has grown tremendously over the past 15 years, but has hit turbulence over the last couple of years. The digital economy has positioned Chinese and Indian private companies to play a leading role in unlocking bilateral growth through a flow of people, capital and ideas. Delhi and Beijing should focus on creating a more facilitative environment to manage growth sustainably and tip the scales in favour of cooperation.

This article was originally published on Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

- Data Sovereignty in Action: Ant Group and Didi Chuxing Case Studies - September 12, 2022

- Pandemic strengthens China’s platforms as infrastructure providers - July 17, 2020

- The bio-surveillance state: an emerging new normal in Asia - May 8, 2020